In the intricate world of language and cultural identity, the way countries adopt and adapt foreign names can be a window into their historical and linguistic landscape. A fascinating example of this phenomenon is seen in the translation and transliteration practices of Korean station names into Japanese and Chinese.

Historically, Japan, as a former colonial power in Korea, has had a significant influence on the Korean peninsula. This influence is evident in various aspects of Korean culture and language, including the use of Hanja (Chinese characters) in Korea. However, post-independence, South Korea has gradually shifted towards using Hangul (the Korean alphabet) exclusively for many aspects of public life, including station names. This shift reflects a broader move towards embracing a distinct Korean identity, separate from the historical influence of China and Japan.

In Japan, there’s a lingering preference among some for the use of Kanji (Japanese characters derived from Chinese) to represent Korean station names. This preference is not just a matter of habit or ease of reading; it’s intertwined with historical and cultural nuances. For example, the Korean station name “동대문역사문화박물관” is transliterated in Japanese as “ドンデムンヨクサムナハパンムルグアン”. This phonetic representation in Katakana, a Japanese syllabary, aims to closely mimic the Korean pronunciation.

However, the Chinese characters for the same station, “东大门历史文化博物馆”, are often perceived by Japanese speakers as more familiar and easier to read. This preference for Chinese characters over phonetic transliteration reflects a deep-rooted historical connection with the Chinese writing system, despite the fact that these characters do not accurately represent the Korean pronunciation.

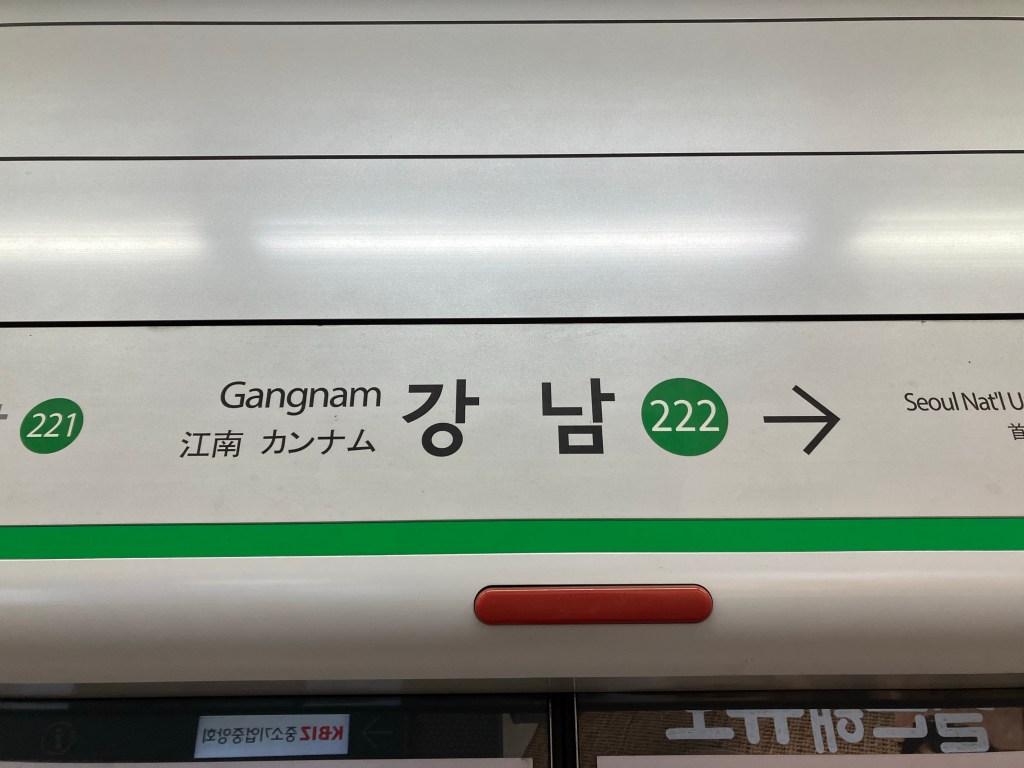

Consider the station name “강남” (Gangnam). In Japanese, it’s transliterated as “カンナム”. If written in Kanji, it would be “江南”, which, while being the historical Hanja for Gangnam, is pronounced “Kōnan” in Japanese, leading to a significant deviation from the original Korean pronunciation. In contrast, the Chinese representation remains “江南”, which closely resembles the pronunciation of “Gangnam” in Mandarin. This example highlights the challenges and nuances involved in translating place names across languages with different phonetic and script systems.

The debate over the use of Hanja or Hangul for Korean station names in Japanese translations is more than a linguistic issue. It’s a reflection of the complex interplay between language, identity, and history. While some argue for the use of Hanja to preserve historical connections and ease of reading, others advocate for Hangul to respect the linguistic identity and pronunciation of Korean names. This discussion also raises an interesting question about the role of translation in preserving the linguistic integrity of names in a globalized world.

One proposed solution for Chinese transliterations is to adopt characters that more closely match the Korean pronunciation, even if they deviate from the historical characters. For instance, “강남” could be transliterated as “刚那木” (Gāngnàmù) in Chinese, prioritizing phonetic similarity over historical character usage.

Ultimately, the way station names are transliterated or translated into different languages is a delicate balance between historical ties, linguistic accuracy, and cultural respect. As languages and cultures continue to interact and evolve in our increasingly connected world, these decisions will remain an important aspect of cross-cultural communication and understanding.